Frequent Halos

Frequent Halos: A Common Atmospheric Phenomenon

Halos, those captivating optical phenomena, grace our skies more frequently than rainbows. Unlike rainbows, which are often associated with rainfall or showers, halos can be observed on average twice a week in various regions of Europe and parts of the United States. The most commonly encountered halos are the 22° radius circular halo and sundogs (parhelia). Let's delve into these frequent halos and explore their captivating nature.

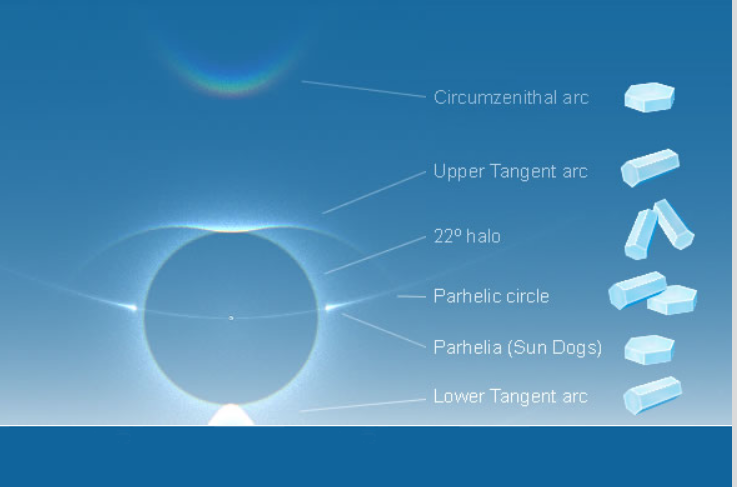

In the realm of atmospheric optics, the HaloSim3 simulation provides an illustrative example of the different components that can manifest during a halo event. In this simulation, the sun takes center stage, surrounded by a mesmerizing 22° halo. Accompanying the halo are sundogs, which flank the sun on either side. Beyond the sundogs lies the parhelic circle, extending through them and occasionally encircling the entire sky at the same altitude as the sun. Additionally, upper and lower tangent arcs appear directly above and below the sun, touching the 22° halo. Finally, high above all, a circumzenithal arc completes the ethereal display. Each of these elements is formed by unique ice crystals, contributing to the intricate beauty of halos.

Halos are not restricted to specific locations or seasons; they can occur throughout the year and in various geographical regions. However, their frequency tends to vary depending on factors such as latitude, weather patterns, and local atmospheric conditions. The frequency of halos also increases in colder climates, where ice crystals necessary for their formation are more abundant.

The 22° radius circular halo is one of the most frequently observed halos. It appears as a large ring encircling the sun or moon at an approximate radius of 22°. This halo is formed when sunlight or moonlight refracts and reflects off hexagonal ice crystals suspended in the atmosphere. The hexagonal shape of these ice crystals plays a crucial role in bending and scattering light, resulting in the formation of the halo.

Sundogs, or parhelia, are another common type of halo that often accompanies the 22° halo. Sundogs manifest as bright spots of light on either side of the sun, creating a stunning celestial display. These colorful patches are caused by the refraction and reflection of sunlight off plate-shaped ice crystals. Sundogs are typically found at the same altitude as the sun, forming a triangle of light with the sun as its apex.

The parhelic circle, extending through the sundogs and occasionally encircling the entire sky, adds an extra touch of enchantment to halo events. This circular band of light is formed by sunlight passing through horizontally oriented ice crystals. As the light enters and exits these crystals, it creates a halo-like effect that can encompass the entire celestial sphere.

The upper and lower tangent arcs, which touch the 22° halo directly above and below the sun, contribute to the complexity of halo formations. These arcs occur when sunlight interacts with specific ice crystal orientations, resulting in the bending and scattering of light in unique ways. The upper tangent arc forms an arc-like shape above the 22° halo, while the lower tangent arc mirrors this pattern below the halo.

Completing the ensemble of halos is the circumzenithal arc, positioned high above all other components. This arc presents itself as an upside-down rainbow or smile-shaped band of colors in the sky. It forms when sunlight interacts with horizontally oriented ice crystals, bending the light at such an angle that it creates this ethereal arc.

In conclusion, halos are captivating atmospheric phenomena that grace our skies more frequently than rainbows. The 22° radius circular halo and sundogs are the most commonly encountered halos, forming an exquisite display in combination with other elements such as the parhelic circle, upper and lower tangent arcs, and the circumzenithal arc. These halos are formed by the interaction of sunlight with ice crystals suspended in the atmosphere, resulting in breathtaking optical effects. So, keep your eyes on the sky, for you never know when a mesmerizing halo might grace your view.

Halos appear in our skies far more often than do rainbows. They can be seen on average twice a week in Europe and parts of the United States. The 22° radius circular halo and sundogs (parhelia) are the most frequent

In this HaloSim3 simulation the sun is surrounded by a 22° halo and flanked by sundogs. Passing through the sundogs and extending beyond them is the parhelic circle. It sometimes encircles the whole sky at the same altitude as the sun. Upper and lower tangent arcs touch the 22° halo directly above and below the sun. A circumzenithal arc is high above all. The ice crystals pictured are those forming each particular halo. Click the simulation text to go to the halo.

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/frequent-halos/">Frequent Halos</a>

-

"Frequent Halos". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on April 27, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/frequent-halos/.

-

"Frequent Halos". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/frequent-halos/. Accessed 27 April, 2024

-

Frequent Halos. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/frequent-halos/.